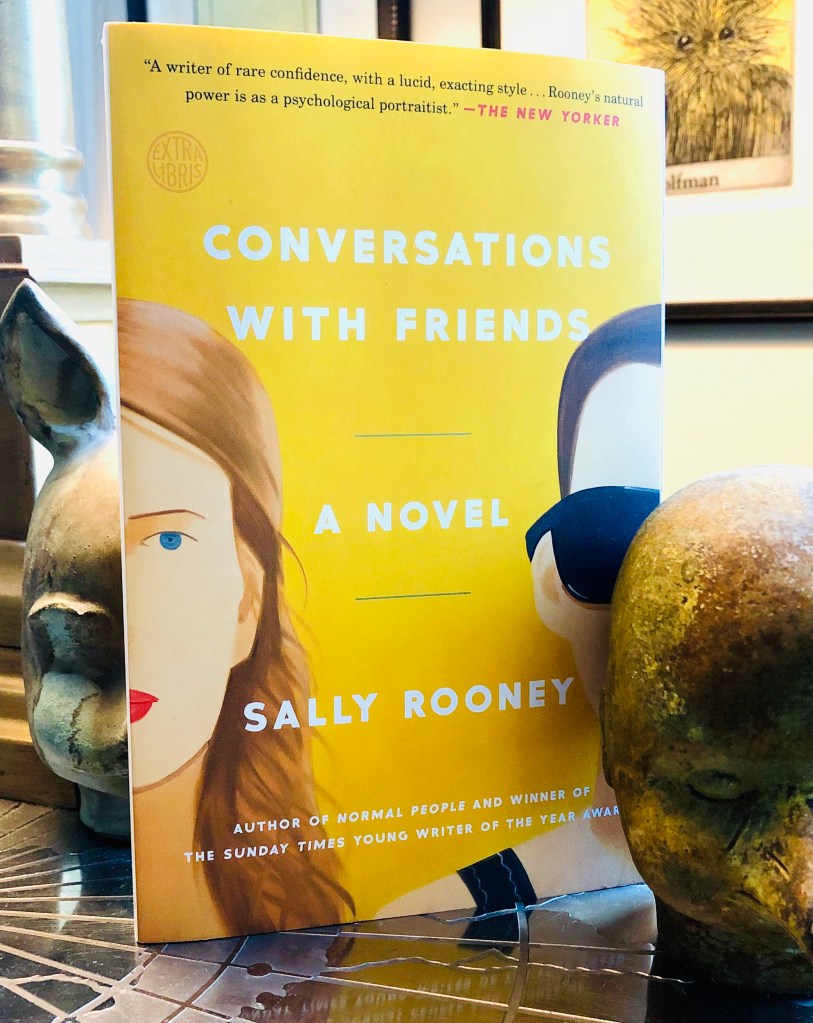

By Sally Rooney

ALL POSTS CONTAIN SPOILERS

One of my small narcissisms: I disdain book fads.

Every year, there are It books, authors the literary cognoscenti have their panties all twisted up about, the new novel that the New York Review of Books declares a Must Read, that every independent bookstore has on it’s Staff Recommendations table (in hardcover), whose author Terry Gross just interviewed last week.

I try to avoid these books.

It’s not that I think they’re all bad books, not at all. Many of them are celebrated quite appropriately (you can count me, for example, among the legions of frothing Elena Ferrante fans).

However, they aren’t all great: some are merely well-publicized. Some are highly experimental, a novel written in all questions, or a novel in one long sentence (these are real things*, and I’ve actually read and loved one of them). Some are more timely than good. Some are fine, but no one will, or should, remember them in five years.

*’The Interrogative Mood‘, Padgett Powell; ‘Ducks, Newburyport

‘, by Lucy Ellman

I’m a snob for the Literary Canon – we’ve talked about this before – and, the truth is, if I spent my time reading every contemporary novel that Michiko Kakutani thought I needed to, I wouldn’t have time to read anything else. So I like to give a book twenty years or so, see how it ages, see whether it’s a flash in the pan or whether anyone remembers it a decade later.

But I make exceptions, for all sorts of valid or stupid reasons. Sometimes a book comes recommended by someone I trust; sometimes it catches my eye; sometimes I have already learned to love the author, or the author keeps being compared to someone else I love (careful with this one – it pretty much never turns out the way you want it to).

And, a few weeks ago, I was going through my old New Yorkers and came across a review of ‘Conversations with Friends‘, a fad book from 2017 that I had successfully avoided. But this review (by Alexandra Schwartz) was called, ‘A New Kind of Adultery Novel‘. I didn’t read the review – I didn’t need to. I’m kind of a creepy little pervert, and there was absolutely no chance I wasn’t going to read a New Kind of Adultery Novel. So this week I read ‘Conversations with Friends’.

Frances and Bobbi went to school together. They dated, and then they broke up, and now they are best friends, college students in Dublin, where they perform spoken-word poetry together. Bobbi is beautiful and outlandish and charismatic. Frances is our narrator, plain and severe, quiet and cerebral. She is a socialist and poet, a bisexual who believes that love has been co-opted by capitalism to wring unpaid labor out of mothers.

One night, the two friends are approached after a show by Melissa, an established artist and photographer. As they begin to get to know her, it becomes clear that, like many people, Melissa prefers Bobbi, and Frances, a little defensively, strikes up a friendship with Melissa’s husband, Nick. Nick is a actor who is semi-famous, handsome and much smarter and more sardonic than he appears. As Frances and Nick begin an affair, the relationship between the four adults becomes more and more complicated until it begins to threaten even the love Bobbi and Frances have for each other.

People went kind of bonkers about ‘Conversations with Friends‘. I myself had multiple girlfriends tell me that I had to read it (that way that people do that makes you want to hit them). And I think I know why, even if I do not perhaps share the wildness of the enthusiasm.

Rooney has a way of writing, a plainness of presentation, which is nearly unique and very effective. This is a little what people are reacting to when they talk about the revolution that Hemingway’s prose represented: the way the spareness of the prose, the lack of adornment, left the reader nowhere to hide.

But Hemingway wasn’t writing about the intricate interiors of human relationships – Rooney is, and so the effect is very different. When people write about feelings, even the feelings of fictional characters, they tend to explicitly frame them as feelings, to soften their reality, to layer them away from fact: “I felt as though…”; “He acted like I was…”; “It was as though I had been…”. We lard our feelings with metaphors and analogies, which are illustrative, but also distancing. Even as we contemplate the feeling, we are imagining something else.

Rooney doesn’t do this. She doesn’t invest in the emotional reality of her characters so much as she simply states it as reality and moves on. She doesn’t interpret or elaborate. Because her prose so fundamentally inhabits the experience of her protagonist, when she does employ similes, they have the effect of turning back inwards, into the mind of Frances.

“Certain elements of my relationship with Nick had changed since he told Melissa we were together. I sent him sentimental texts during daytime hours and he called me when he was drunk to tell me nice things about my personality. The sex itself was similar, but afterward was different. Instead of feeling tranquil, I felt oddly defenseless, like an animal playing dead. It was as though Nick could reach through the soft cloud of my skin and take whatever was inside me, like my lungs or other internal organs, and I wouldn’t try to stop him. When I described this to him he said he felt the same, but he was sleepy and he might not really have been listening.” (p. 232)

All of which, because of the bareness of the prose, has the effect of making Frances a little hard to take.

Which, ok, a brief temper tantrum on my part: I really, really hate when people object to books because the characters aren’t “likable” or because “there’s no one to root for”. I think it’s infantile to assess books the same way you pick friends: by how much you want to have a beer with them. If you’re only reading books that have people you explicitly like, fuck off to ‘The Babysitters Club’ and let the adults talk.

So it’s not a problem for me that I don’t like Frances (or Bobbi) at all. But, let’s be real: a book about complicated, narcissistic, chilly people hurting each other is a different emotional experience than one that involves heroic, kind people battling evil. ‘Conversations with Friends‘ is a very different book than, say, ‘The Hobbit’. I understand why people reacted to strongly to this book: it’s emotionally bracing. But, like most things that are bracing (a stern talking to from a loved one, a leap into an ice cold lake), it wasn’t pleasant until it was done.

And maybe it wasn’t even pleasant after it was done? But that’s OK – pleasant is emphatically not the point.

Rooney is experimenting with a different way of communicating about emotions. She’s trying to show the interior life of a young woman, show us her anger, and her loneliness, her fear and her attempts at love, the way that she herself experiences them. The prose is meant to be immersive – there is no framing here, to give you distance. And because Frances is angry and lonely and scared and receives no consolation from love, the experience is a little bleak, a little real, a little rough and almost totally undigested.

It’s tough, because I know I was supposed to love ‘Conversations with Friends‘, and so I really, really didn’t want to. When I finished it, I thought it was competent and over-rated.

But I’ve had a couple days to think on it, to get some emotional distance from Frances, and I think maybe I did love it. Or I really, really appreciated it? Or I saw the same thing all the fart-sniffing New York literary whosits saw: a very smart new writer trying something different. And succeeding.