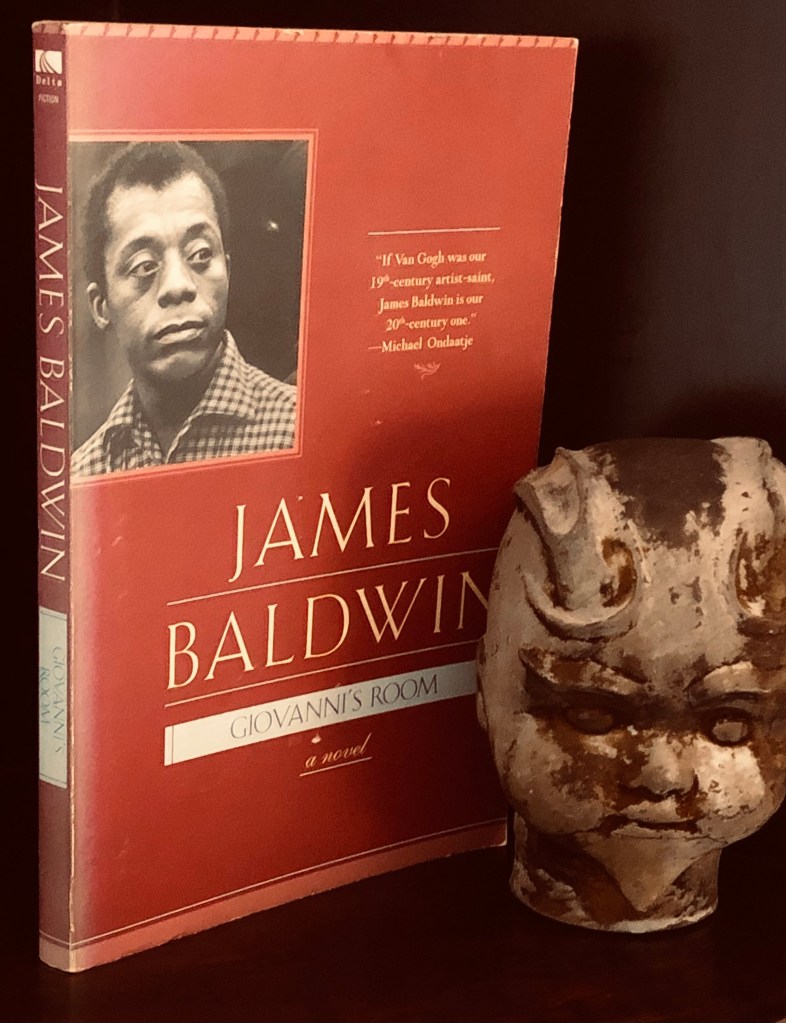

By James Baldwin

ALL POSTS CONTAIN SPOILERS

Years ago, a handsome young man, with whom I had never had sex of any kind, told me that our relationship reminded him of ‘Giovanni’s Room‘*. When I asked, “Which of us is Giovanni?” he said, “You are.”

(*I still haven’t had sex of any kind with him.)

‘Giovanni’s Room‘ is a novel by James Baldwin, who is probably the best American writer who has ever lived. It’s a story about two men who fall in love in Paris: David, an American, who is waiting for his fiancée to return from her travels, and Giovanni, an Italian bartender. They spend a summer living in Giovanni’s decrepit room, where David’s crisis of identity deepens as Giovanni comes more and more dependent on him. When David leaves Giovanni and returns to his fiancée, Giovanni has a slow-motion breakdown, which will eventually culminate in his imprisonment and execution.

It’s a beautiful novel, but I was offended by the comparison, because Giovanni is many things I do not find myself to be: he is clingy, passionate, romantic, melodramatic, and a drunk. According to my personal value system, it’s basically better to be a murderer than to be clingy and emotional, and so I deeply resented the implication that I was the Giovanni in any relationship. On the contrary, I have spent most of my relationships feeling very much like David: interior, ambivalent, cold, held back from normal human intimacy by profound self-loathing. I have held the comparison against that young man for almost twenty years now.

But I reread ‘Giovanni’s Room‘ the other day, and I see now that, in my outrage, I misunderstood what it is really about. I suppose I thought that it was about how destructive passion can be, about how a nature, consumed with love and without other ballast to steady it, could spin off into madness. I was fooled by the oldest trick in literature: I was paying attention the wrong character. I thought that ‘Giovanni’s Room’ was about Giovanni.

‘Giovanni’s Room’ is about David. It isn’t a novel about passion, or madness – it’s a novel about alienation, about the destruction of the possibility of love by hatred. David, who has spent his life in full flight from his very self, hates himself so completely that the love of other people, which he needs like water, feels like chains to him.

Baldwin doesn’t explicitly frame David’s self-loathing as internalized homophobia, and, though that is clearly part of it, I do not think he intended that David’s condition be that simple. David has been warped by a feeling that certain of his longings are “wrong”, yes, but he is also economically, culturally, and familially alienated as well. He is lost, trapped being a person he despises and unable to break free.

What David comes to know, what I have also come to know and the reason that I identified so strongly with David when I first read ‘Giovanni’s Room‘, is that, when we truly hate ourselves, we are unable to sincerely love anyone else. And when you are incapable of loving other people, the love they offer you will always feel like a hair shirt: irritating, painful, constricting, external. You will seek it out – you are lonely, after all – but when you receive it, you will immediately feel straight-jacketed and embarrassed by it. The people who love you are so earnest, so intense, that it is difficult to look them in the eye. David flinches from Giovanni (I flinched from Giovanni) not because Giovanni is so extra, but because Giovanni is whole-hearted and David, who’s own heart is consumed by hating himself, is mortified by that.

Like most truly great books, ‘Giovanni’s Room‘ is even more beautiful upon rereading. I have always found James Baldwin breathtaking, one of those authors who make me feel that reading their words is a privilege. He has always possessed a special insight into human suffering, no less clear-eyed because it is merciful, and he has the writerly power to express his insights with devastating effectiveness. And I discovered, upon rereading, that Baldwin tells us exactly what it means to be Giovanni:

“Perhaps, everyone has a garden of Eden, I don’t know; but they have scarcely seen their garden before they see the flaming sword. Then, perhaps, life only offers the choice of remembering the garden or forgetting it. Either, or: it takes strength to remember, it takes another kind of strength to forget, it takes a hero to do both. People who remember court madness through pain, the pain of the perpetually recurring death of their innocence; people who forget court another kind of madness, the madness of the denial of pain and the hatred of innocence; and the world is mostly divided between madmen who remember and madmen who forget. Heroes are rare.” (p. 25)

Giovanni goes mad through remembering; David goes mad through forgetting.

It’s funny, getting older. I was furious when that young man told me I reminded him of Giovanni, but I know now that he wasn’t insulting me at all. Quite the contrary, I believe he knew, young as we were, what Baldwin knew: that it is better, in the end, to be Giovanni, because Giovanni at least knows his own heart. David knows nothing.

I also know that, sadly, that young man was wrong about me. I am not Giovanni – I am David, I always have been.

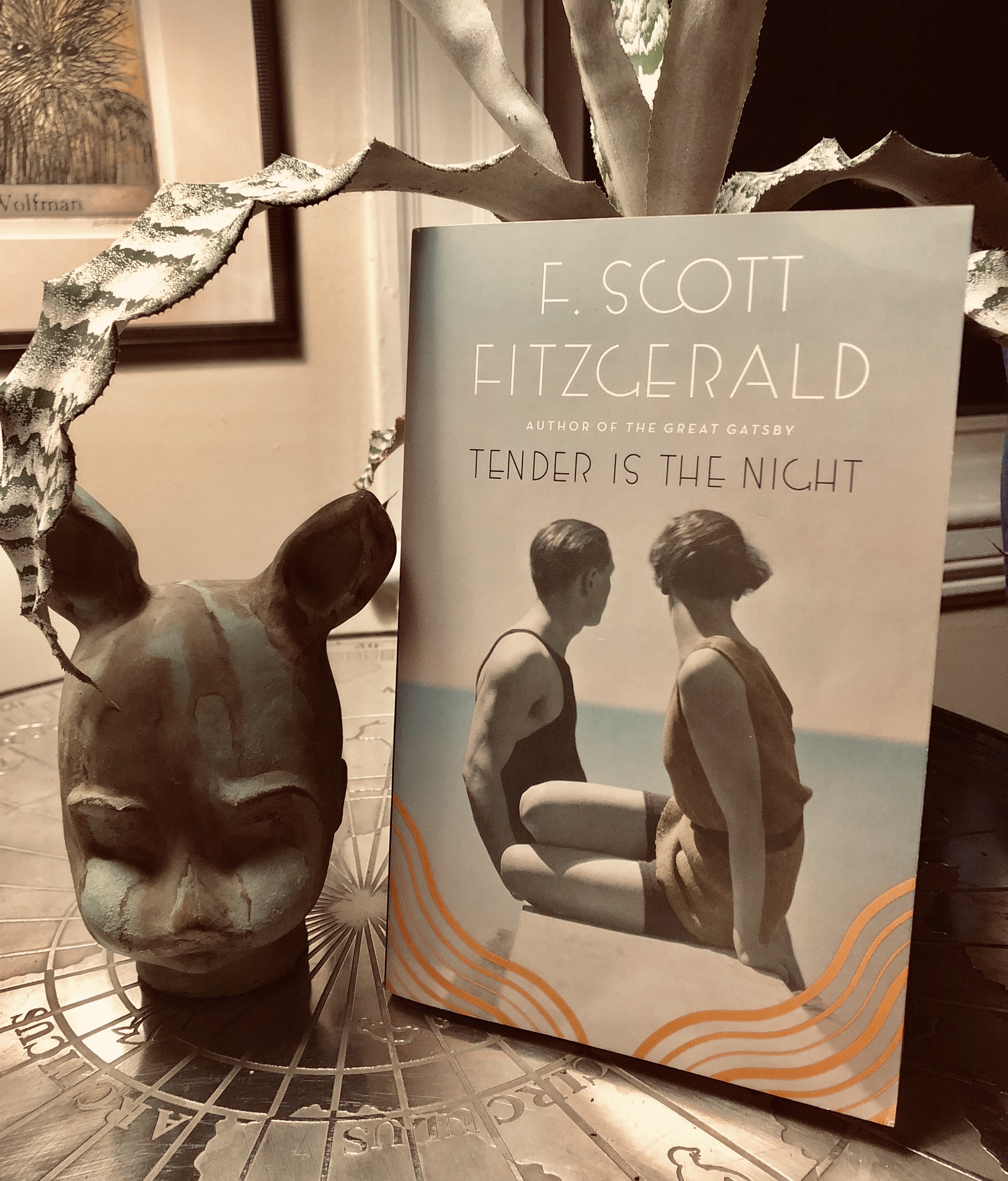

I am hesitant to do this, because my feelings about F. Scott Fitzgerald are complicated, and heavy. But Fitzgerald towers over American letters, blotting out the sun before it can reach other authors. He is read ubiquitously, but narrowly: it is almost impossible to graduate from an American high school without having read ‘

I am hesitant to do this, because my feelings about F. Scott Fitzgerald are complicated, and heavy. But Fitzgerald towers over American letters, blotting out the sun before it can reach other authors. He is read ubiquitously, but narrowly: it is almost impossible to graduate from an American high school without having read ‘