By Nicola Griffith

ALL POSTS CONTAIN SPOILERS

Please join me, if you will, on a long and tortured metaphor.

Stories are like dishes. They are made up of ingredients: premise, plot, characters, writing, &c. Some dishes are very complex (lots of different plots and characters) – some are very simple. Complexity does not necessarily predict success: a bad story can have all the characters it wants, it will still be bad.

Like dishes, stories can be dominated by one or two components and still be very good. Think about the murder mystery: all plot, with, at best, a single charismatic detective for continuity. Most fantasy novels are the same: it’s all plot, but with some premise thrown in. As in dishes which are dominated by a single component, in order for stories like this to work, the main component needs to be really good: you can’t make a good omelet with rotten eggs.

And like dishes, stories are made up not just of major components, but also require seasoning. If characters and plot are major ingredients, then all the little embellishments which give a story depth and attraction are seasonings: well-imagined details, zippy dialogue, beautiful language.

And also like dishes, stories can be ruined by over-seasoning. You can have great characters, great plot, beautiful setting, but if you get carried away on, say, describing lush landscapes, then you can alienate your readers and make your prose a slog.

And the reason that I have dragged you on this arduous metaphor is because today I want to talk about one of the most difficult seasonings in literature: historical verisimilitude.

Books are for readers – that is their intended audience. That doesn’t mean that books should be lowest-common-denominator products, aimed simply at gathering the most eyeballs. But books should be basically intelligible to their readers – that’s really the bare minimum.

A little antiquated vernacular is fine – most people can pick around and it get it from context clues. And some historical detail is appreciated – it adds color to the world. But, at a certain point, too much extraneous detail, or strange vocabulary, is cumbersome and alienating. I should be able to read a paragraph of your text without, say, having to check the glossary eight times, or having to read the dialogue out loud because that is the only way to understand the text. I should be able to read your novel without learning the name of every single Dark Ages village in England.

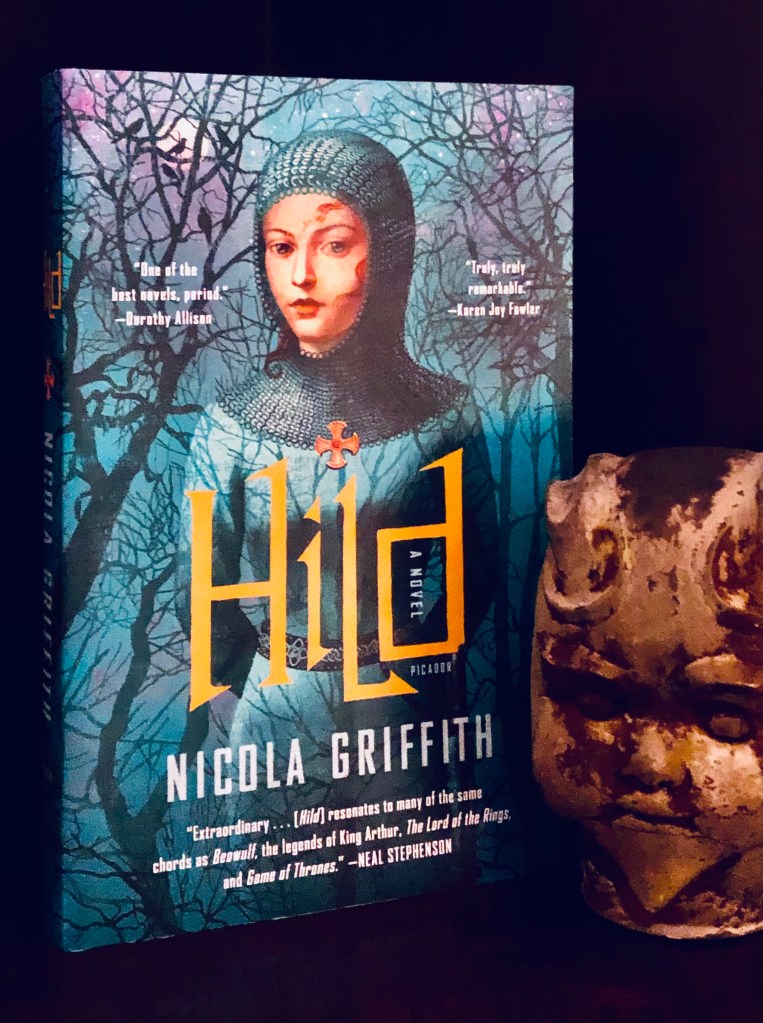

And we’re talking about this because I just finished ‘Hild‘ by Nicola Griffith and I’m frankly exhausted.

‘Hild’ is the imagined backstory of Hilda of Whitby, an English saint who lived in the 7th century. Her childhood is, from what I can tell, entirely imagined by Griffith, but the research which informs the setting is impeccable: detailed, thorough, and accurate.

It is also, however, cumbersome: Griffith has, in my opinion, crossed the line between enriching the novel and leeching the reader’s bandwidth, and her historical detail, especially her use of language, takes more than it gives from reading this novel.

Let me give you an example.

“Hild persuaded Pyr that none would think him soft if the Loid workers were fed and sheltered, for a healthy Loid worked faster. And besides, she spoke for the king when she said that in Elmet now there were no more Anglisc, no more Loid, there were only Elmetsætne. She set Morud to making sure all grumbles reached the right ears.

More people, Loid and Anglisc, straggled in and sought her out, some to swear to her, some just to see for themselves the tall maid who called them all Elmetsætne. The daughter of a hægtes and an ætheling, some said – no, a wood ælf and a princess, said others – though that didn’t stop them wanting to touch her hem or catch up a fallen hair for luck.” (p.292)

Or how about this:

“Hild had helped work out how the new wool trade would run, but even she was astonished at its efficiency. Sheep sheared in every royal vill, from the Tine valley to Pickering to the wolds to Elmet. Fleece sorted and sent by grade to rows of huts in Aberford, or Flexburg by the Humber, or Derventio. Armies of women to separate out the staples, to mix soapwort, urine, and pennyroyal to wash out the grease. Children to lay the washed wool in the sun to dry, to watch and turn it and to drive off the birds who liked to steal it. Men to barrel and cart oil and grease to the vills to make the fibre more manageable for the first finger-combing and sorting. Smiths hammering out double-rowed combs and woodworkers shaping wooden handles, for women to comb out wool in the new way, the better way, a comb in each hand. Carpenters to build the stools and tables. Bakers to bake the bread so the wool workers could work. Lathe workers to turn the spindles and distaffs – the long and the short – and, everywhere, women and man making spindle whorls and loom weights of clay and lead and stone, of every shape and size and heft.” (p. 383)

I chose these passages not because they are unusual – the entire book really is like this – but because I think they are particularly emblematic both of that makes ‘Hild‘ singular and, often, magical, but also what is trying about it. Griffith’s writing is dense and spare. Her attention to detail is incredible, but she is totally unforgiving: she will not define, introduce, or repeat herself. If you haven’t grokked what an Elmetsætne is, you can go screw (or check the gloss, for the sixth time that page). There are too many proper names, and they are too similar. Every clause has a discrete, private meaning, and they work against each other. Meanwhile, as you are drowning in detail, you are often unable to spot the action when it happens, and because the entire story is told in this same, low monotone, there are no signifiers helping you to notice what’s important.

And it’s a shame, because I think it’s a pretty good book. It’s certainly an interesting project to have undertaken, and the depth of knowledge and imagination is almost overwhelming. It is also a masterpiece of mood – it is a low, gray novel, very beautiful, naturalistic and wild. But Griffith is too eager to show you the depth of her knowledge. The detail is not for you, to add to your sense of the story – it is for her, to show you how much she knows.

‘Hild‘ is over-seasonaed. Vernacular, vocabulary: these are elements which can add richness to a work of imagination. However, the more you disrupt a reader’s immersion in your story, the more you risk becoming a chore for them. Griffith goes too far for me: I am impressed by her work, but I am also alienated by it. I find myself able to feel a lot of respect for it, but no affection. By the end of the book, I felt the way I feel during a bad run: determined to finish, certain that I am doing the right thing, that I will be better for it in the end, but heavy, tired. Completion has become the goal – the journey has no joy.